Papyrus as a Symbol of Egypt

advertisement

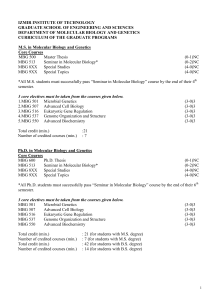

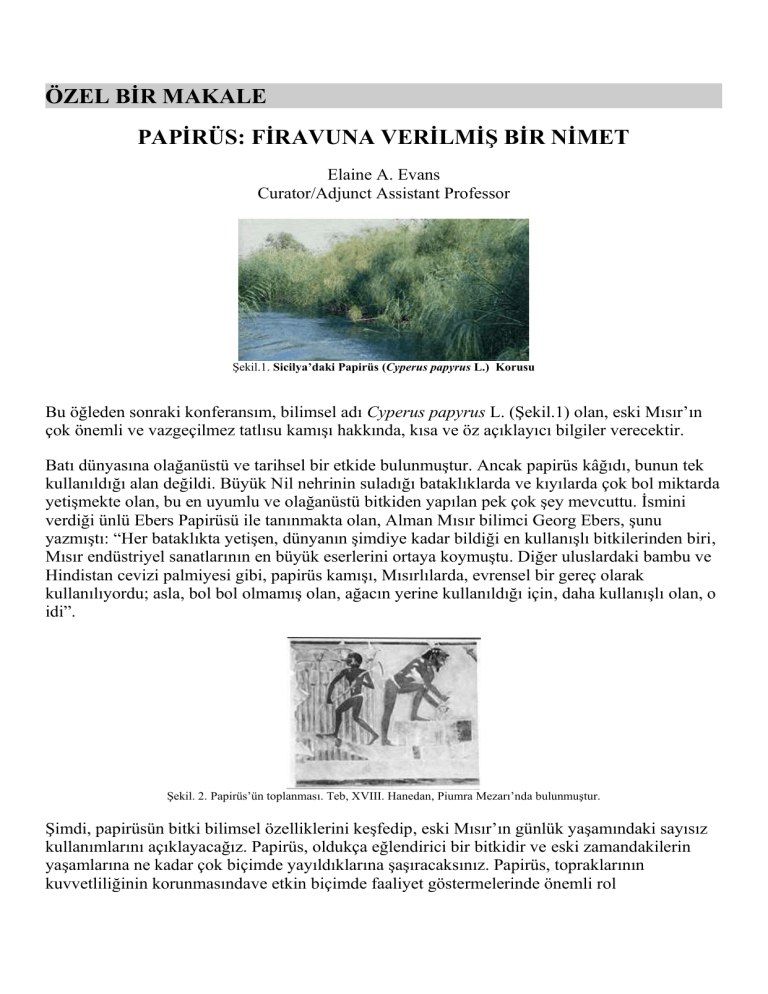

ÖZEL BİR MAKALE PAPİRÜS: FİRAVUNA VERİLMİŞ BİR NİMET Elaine A. Evans Curator/Adjunct Assistant Professor Şekil.1. Sicilya’daki Papirüs (Cyperus papyrus L.) Korusu Bu öğleden sonraki konferansım, bilimsel adı Cyperus papyrus L. (Şekil.1) olan, eski Mısır’ın çok önemli ve vazgeçilmez tatlısu kamışı hakkında, kısa ve öz açıklayıcı bilgiler verecektir. Batı dünyasına olağanüstü ve tarihsel bir etkide bulunmuştur. Ancak papirüs kâğıdı, bunun tek kullanıldığı alan değildi. Büyük Nil nehrinin suladığı bataklıklarda ve kıyılarda çok bol miktarda yetişmekte olan, bu en uyumlu ve olağanüstü bitkiden yapılan pek çok şey mevcuttu. İsmini verdiği ünlü Ebers Papirüsü ile tanınmakta olan, Alman Mısır bilimci Georg Ebers, şunu yazmıştı: “Her bataklıkta yetişen, dünyanın şimdiye kadar bildiği en kullanışlı bitkilerinden biri, Mısır endüstriyel sanatlarının en büyük eserlerini ortaya koymuştu. Diğer uluslardaki bambu ve Hindistan cevizi palmiyesi gibi, papirüs kamışı, Mısırlılarda, evrensel bir gereç olarak kullanılıyordu; asla, bol bol olmamış olan, ağacın yerine kullanıldığı için, daha kullanışlı olan, o idi”. Şekil. 2. Papirüs’ün toplanması. Teb, XVIII. Hanedan, Piumra Mezarı’nda bulunmuştur. Şimdi, papirüsün bitki bilimsel özelliklerini keşfedip, eski Mısır’ın günlük yaşamındaki sayısız kullanımlarını açıklayacağız. Papirüs, oldukça eğlendirici bir bitkidir ve eski zamandakilerin yaşamlarına ne kadar çok biçimde yayıldıklarına şaşıracaksınız. Papirüs, topraklarının kuvvetliliğinin korunmasındave etkin biçimde faaliyet göstermelerinde önemli rol oynuyordu.Mısır firavunlarına kutsanmışlardı. Papirüs, insanlığın aşina olduğu en eski bitkilerden biridir. Kökeninin, Mısır olduğuna inanılmaktadır. Uzun, narin bitkinin tarihi; Hanedan Dönemi’nden öncesine uzanmaktadır. Kültürel gelişimlerinin yüksek olmaları sayesinde, böylesine doğal çevrelerine uyumlu olan, eski Mısırlılar, bunların pratik kullanımlardaki değerlerini ve potansiyellerini açığa çıkarabiliyorlardı. Tüm hanedan dönemleri boyunca, papirüs, Firavun ve halkına tatmin ve yarardan başka hiçbir şey getirmemiştir. Eski zamanlarda, papirüsün toplanmasını ve üretimini tasvir etmekte olan, mezar duvarı resimlerinden, bitkinin yarattığı faaliyeti, daha açık biçimde, gözümüzde canlandırabiliriz (Şekil.2). İşçiler; bataklıklardan, bitki saplarını söküyor; saplarını, demetler halinde bağlıyorlar ve işlenmek üzere, atölyelere taşıyorlardı. Gezginler ve Asılsız Bitki İlk zamanlarda, Diğer eski zaman kültürlerinden ziyaretçiler, Mısır’a geliyorlardı ve her yerde bu kadar bolca yetişen gür Cyperus papyrus bitkisinden etkileniyorlardı. Eski Yunan tarihçilerinden Herodot’a (MÖ 450 dolayları) göre, papirüs, “bataklıklardan koparılıyor, tepesi kesilerek atılıp diğer uçlara dönüştürülüyor ve alt kısmı…yeniliyor ya da satılıyordu”. Elimizde, Romalı doğa bilimci Yaşlı Pliny’ye (MS 23-29)ait eski bir açıklama da bulunmaktadır ve kendisi, yazmış olduğu “DoğaTarihi” ansiklopedisinin XIII. Kitabı’nın 71. sayfasında, Nil Nehri’nin15 fit (4,57 m) yüksekliğe ulaşan bataklıklarında ve durgun sularında yetişen bitki hakkında bilgi vermiştir. Şekil. 3. 1798’de, Piramitler’deki Napolyon’un askerleri. Kaynak: La Description de l’Égypte. Mısırlıların Djet veya tjufi adını verdiği görkemli, yeşil bitki; günlük hayatlarında, son derece kullanışlı bir rol oynuyordu, ancak günümüzde, üzücü biçimde, Mısır’da, neredeyse tamamen ortadan kalkmıştır. Bunun, tam olarak, ne zaman gerçekleştiği bilinmemektedir. Ancak bazıları, Napolyon, askerleriyle birlikte,Mısır’a gelmeden önce, asıl bitkinin neslinin, Nil nehri üzerinde tükendiğine inanmaktadır (Şekil.3). Bitki; içerisinde, Mısır’ın bitki örtüsüne (flora) ve direyine (fauna) adanmış bir bölüm bulunmakta olan, Napolyon’un 19. Yüzyıl başlarındaki ünlü La Description de l’Égypte başlıklı Fransızca eserinde kayıtlı değildir Bu durum, bazı bilim adamlarının, bitkinin ortadan kalktığına inanmasına neden olmuştur. Üstelik, bitki bilimciler içerisinde de anlaşmazlığa yol açmıştır. Konu hakkında, pek çok soru sorulmuş ancak bunların pek azına yanıt verilmiştir. 982 yılında, İbn Gulgul gibi, ilk Arap yazarları,Nil bataklıklarında boyu uzayan bitkiye değindiler. Çok daha sonra, Fransız doğa bilimcisi Pierre Belon, 1546-49’da; İtalyan doktor ve bitki bilimcisi Prosper Albinus ise, daha sonra, 1580’de, Mısır’daki papirüsü işaret etti. Ancak ünlü İsveçli kaşif ve bitki bilimcisi Fredrik Hasselquist, 1749-50 yıllarındaki gezisinde, bitkiye rastlamadı. Ancak 1790’daki öncü kitabı Select Specimens of Natural History collected in Travels to discover the Source of the Nile in Egypt, Arabia, Abyssinia, and Nubia’da (Mısır’daki, Arabistan Yarımadası’ndaki, Etiyopya’daki ve Nubiya’daki Nil Nehrini Kaynağının Keşfi Gezilerinde Toplanan Seçme Doğa Tarihi Örnekleri), İskoç gezgin James Bruce (1730-1794), Mısır’daki papirüsün hakkında yazmış ve kökeni konusundaki görüşlerini şöyle ifade etmişti: “Papirüs, bana, daha önce, buraya, Etiyopya’dan inerekgelmiş ve Yukarı Mısır’da kullanılmış gibi görünmektedir…” Fig. 4 Engraving of Papyrus, circa 1790. From J. Bruce, Select Specimens of Natural History…. London 1790. Bruce, bitkiyi ayrıntılı olarak açıklamamış, ancak gravür tekniği ile yapılmış resmi (Şekil.4), kitabında, bir çizim olarak görünmekte ve tercihen, Mısır’da, birkaç yıl sonra yetiştiği keşfedilen bitki ile karşılaştırmaktadır.1820-1821 yıllarında, Prusya ordusu subayı olan, Baron Heinrich C. M. Minutoli (1772-1846), bir zamanlar, yüz ölçümü, 660 milkarelik (1.709,40 km2) Manzala Gölü kıyısında olmasının yanında, Nil Nehri’nin doğu kıyısında ve Kahire’nin 125 mil (201 km) kuzeydoğusunda olan, Dimyat şehrindeki Nil Deltası’nın çeşitli yerlerinde yetiştiğini bulmuştur. Ancak, 1897’de, Mısır bitkileri hakkındaki birkaç kitabın yazarı olan, seçkin Fransız bitki bilimcisi G. Delchevalerie; yazılarında, Mısır’da, papirüs bitkisinin tamamen tükendiğine değiniyordu. Kendisi, şunu ifade ediyordu: “1872’de, Mısır’a getirilen 12 bitkiyi verdiğimiz ve bunları, Kahire’nin Choubra (Subra) mahallesine ve Kahire’deki diğer bahçelere diken, Paris’teki Lüksemburg Bahçesi’nin Baş Bahçıvanı olan, A. Riviere’ye mahkûm kalmıştık.” Bazı bilim adamları, Mısır’da yetişen türün, günümüzde, muhtemelen, Fransa’dan getirilen bu bitkilerden türediğine inanmaktadır. Ancak, bitki bilimciler Vivi Täckholm ve Mohammed Drar, yine de, 1950 yılına ait Flora of Egypt (Mısır Bitkileri) kitaplarında, bir zamanlar, tükendiğine inanılan Cyperus papyrus’un Natrun Vadisi’ndeki Umm Risha Gölü’nde yeniden keşfedildiğini iddia etmişlerdir. Ayrıca, Kahire’deki Papirüs Enstitüsü’nün Müdürü olan, Hassan Regab, 1980 yılındaki kitabı Le Papyrus’ta, eski zamanlardan kalma bitki olduğuna inanmakta olduğu, Natrun Vadisi papirüsünü yakından incelemiş ve Nubiya’daki ve Sudan’da bulunanlarla aynı olduğunu keşfetmiştir. Cyperus papyrus, dünyanın çeşitli yerlerinde tanınan, muhtemelen, 4.000 türe sahip geniş bir çim benzeri bitki ailesi olan,Cyperaceae(Sazgiller) ailesine mensup bir türdür. Bir zamanlar, Nil nehri boyuncaki bataklıklarda bol miktarda yetişmiş olan, uzun çiçekli bir sazdır. Bitki, beslenmesini gerçekleştirmekte olduğu, zangin, sulak ve çamurlu alanlardaki bu bereketli sularda iyi gelişiyordu. 1875’te, W. T. Thiselton-Dyer, bunu, şöyle açıklamaktadır: “Ortadan kaybolmasının sebebini, muhtemelen, herhangi bir iklim değişikliğinde değil,muhtemelen, suyunun dönemsel yükselişi ve alçalması halinde, nehrin fiziksel koşullarında aramakgerekir – insan müdahelesi olmadan da, nedeninin, buna dayandırılması mümkün değildir. Ayrıca, Delta, alüvyonla doldu ve bu da, MÖ 12. yüzyılda, onun, tuzlu bir bataklığa dönüşmesine yol açtı. Böylece, bir tatlı su bitkisi olan, papirüs, kaçınılmaz olarak yok oldu. Çok daha sonra, papirüs dışındaki malzemelerden kâğıt üretildiğinde, artık, bitkinin tarımının yapılmasına gerek kalmadı ve nesli tükendi. Papirüsün Özellikleri Hassan Regab tarafından araştırılan Cyperus papyrus, onun mükemmel özelliklerinin daha iyi anlaşılması için, iyi bir örnek oluşturacaktır. Hassan Regab, Enver Sedat’tan, Mısır’a önemli katkılarından ve özellikle Mısır papirüsü ile yaptığı çalışmalardan dolayı, Mısır Cumhuriyeti Baş Nişanı’nı almıştır. Cyperus papirüsüne yakından bakış, onun temel bitki bilimsel özelliklerinin birkaçına odaklanmamızı sağlayacaktır. Hassan Regab, bitkiyi, enine boyuna açıklamasına rağmen, anlaşılması güç hücre sistemi haricinde, çok karmaşık yapısının tek bir kısmı aydınlatılacaktır. Şekil. 5. Papirüs bitkisinin şemsiye biçimindeki çiçek durumu. Kaynak: H. Ragab, Le Papyrus. Cairo 1980. Olgun, açık haldeki çiçeklerden oluşan şemsiye şeklindeki çiçek durumu (Şekil.5); sapından birleşen ince, çubuğumsu sürgünlerden oluşmaktadır. Şemsiye şeklindeki çiçek durumu ya da ardışık sarkık gövdelerindeki tam başakçık çiçek kümesi veyahut sayısız ince şemsiye şeklindeki ışınlar, şemsiye şeklindeki çiçek durumunun, güneş şemsiyesine ya da yelpazeye benzemesine yol açar. Her bir bitkinin, şemsiye şeklindeki çiçek durumunu desteklemekte olan, uzun, düzgün bir sapı vardır. Saplar, 4 m ya da daha fazla yüksekliğe ulaşır. Şekli; üç köşeli, dayanıklı, pürüzsüz, yapraksız, düğümsüz, konik olup; geniş, mızrak şekilli yapraklarla çevrili olduğu, taban kısmı kalındır. Dirençli yaprakları, sapın tabanındadır. Bu kınımsı pullar, Cyperus’un pek çok türünde farklılık göstermektedir. Cyperus papirüsü durumunda, taban yaprakları, bataklığın suyuyla çevrili olup kestane renklidirler (Cyperus’un diğer türlerinde, yapraklar, suyun üzerinde, çok büyük yüksekliklere ulaşacak biçimde gelişirler ancak yeşil renklidirler). Bunlar, güneş ışığında, klorofilin fotosentezi başlatması ve karbon dioksitin ve suyun karbonhidratlara çevrilmesi işlevini görmektedirler. Ortalama adedi, 7 olmakla birlikte,bordo renkli yapraklarının sayısı, 5-9 adettir. Yapraklarının en uzun olanı, gövdeye en yakın olanıdır Şemsiye şeklindeki çiçek durumları ve saplar nereden gelişmektedir? Bunlar, üst yüzeyinden, yapraklı sürgünleri ve alt yüzeyinden ise, sürgünleri çıkaran, yatay, köke benzeyen bir gövde olan, rizomdan gelişmektedirler. Rizomlardan bahsettiğimizde, çoğunlukla, kalın ve beslenme için gereken kaynakları içeren, genellikle, yatay konumda olan, bitkinin ilk büyümesini gerçekleştiren, toprak altındaki kökü aklımıza getiririz. Çek Mısır bilimcisi Jaroslav Cerny rizomu şöyle açıklamaktadır: “…tamamen toprağın içine batmış halde bulunmaktadır, ancak birçok gövde, tek bir kökten filizlenmekte ve çoğunlukla, 3-6 m yüksekliğe ulaşmakta ve tepesinde, çiçekler bulunmaktadır. Fig. 6. H. Ragab’a göre, rizom (Le Papyrus. Kahire, 1980) Resim (Şekil.6), eski, çürüyen bir rizomdan yatay olarak, genç bir rizomun gelişimini göstermektedir. Dik sürgünler, minik köklerin desteklerinin, havalandırılmış genç gövdelere geliştikleri yerlerde ortadan kalkmaktadır Başak, ortadaki saplarından filizlenmekte bulunan, dallanan, başağımsı tomurcuklardan oluşmakta olan, uzun bir çiçek kümesidir. Başağın desteği, çeşitli uzunluklarda gelişmektedir ve tomurcuklar, her bir sapta, sayıca değişmektedirler. Her bir başak, kabuğa benzemekte olan, 20 kadar çiçek vermektedir. Bunlarda, ne çanak yapraklar ne de petaller; yani, ne dıştaki taban yaprakları ne de içteki petaller veya yapraklar yer almamaktadır. Şekil. 7. Şemsiye biçimindeki çiçek durumunun gelişimi. Kaynak: H. Ragab, Le Papyrus. Cairo 1980. Şemsiye biçimindeki çiçek durumunun gelişiminin 3 safhası vardır (Şekil.7). Sap yapısı, gövdenin kap benzeri kalın uçlu yapraklarından açılmaktadır. Minik, ince tekerlek parmakları ya da yapraklar, kınlarından, yelpazeye benzeyen şemsiyeyi oluşturacak biçimde çıkarlar. Bir başak ya da çiçek kümesi, ince, sarkık saplardaki birleşme noktalarının her birinin üzerinde toplanmaktadır. Papirüs Kağıdı Elbette, eski Mısır’ı düşündüğümüzde, papirüs kâğıdı aklımıza gelir. Mısır, onun mucidiydi. Gerçekten, muhtemelen, hakkında, hiçbir şey bilmesek dahi, kağıt olarak, papirüsü düşünürüz. Aslında, papirüsün ana önemi, yazıma ve resimle göstermelere uygun yüzeyinin olmasıydı. Yazma gereci olarak, papirüsün, Mısır’da, tam olarak ne zaman yaratıldığı, halen bilinmemektedir. Mısır ve eski dünya tarihi hakkındaki pek çok şey, papirüs kâğıdına kayıtlı olarak, elimize ulaşmıştır. Ayrıca, bir kitabın resmi olarak kabul edilmekte olan, bir papirüs rulosunun resim yazı simgeleriyle açıklanmış olarak, MÖ 3.100 dolaylarında, I. Hanedan tarafından kullanıldığını biliyoruz. Bu tür papirüs ruloları, ilk yerleşim yerlerinde bulunmuştur. I. Hanedan’dan, Hamaka’nın mezarında, bir papirüs rulosu keşfedilmiştir, ancak, ne yazık ki, boştu. Giza yakınındaki Kral Neferirkere’nin tapınağında, artık, Kahire, Berlin ve Londra’daki University Colloge’de bulunmakta olan, MÖ 2477-2467 yıllarına ait, V. Hanedan döneminden kalma, küçük parçalar bilinmektedir. Bu nedenle, Erken Hanedan ve Eski Krallık dönemlerinde, bunun üretildiğini biliyoruz. Şekil. 8: Kha’nın Papirüsü. Prof. A. Basile’in kopyası. Fazlasıyla, papirüs kağıdı, pek çok yerde ancak çoğunlukla mezarlarda bulunmuştur. İlk örneği ise, muhtemelen, Teb’deki Deyrü'l Medine’de, İtalyan mısır bilimcisi Ernesto Schiaparelli’nin yaptığı kazılarda, 1903-1920 yıllarında,(Yeni Krallık, XVIII. Hanedan, MÖ 1386-1349 dolaylarına ait)ustabaşı Kha ile karısı Merit’in mezarındaki bir tabutta bulunmuştur. 16 m uzunluğundaki papirüs, aslı Torino, İtalya’daki Mısır Müzesi’nde bulunmakta olan “Ölüler Kitabı”nı tasvir etmektedir. 1989’da, Tivoli, İtalya’daki Museo Didattico del Libro Antico’nun (Antik Kitap Eğitimi Müzesi) müdürü Profesör Antonio Basile; özellikle, Knoxville, Tennessee Üniversitesi, Frank McClung Müzesi Mısır Galerisi için gerçek papirüsün ilk metresinin tam bir kopyasını yapmakla görevlendirildi. Papirüsün bir bölümü, Ahiret’teki gölgeliğinin altında oturan büyük Ölüler Tanrısı Osiris’in huzurunda, ölü Kha ile karısını resmetmektedir (Şekil.8). Papirüs ruloları ve onun üzerindeki belgeler, tahta sandıklarda, kavanozlarda ya da kutsal heykellerde saklanıyordu. Sandıklar, çoğunlukla, yazmanların önündeki yerde duruyor biçimde simgeleniyordu. Mısır’ın Gebelein V. Hanedan mezarından gelen hemen hemen tamamlanmış papirüs ruloları, Teb’deki III. Ramses’in XIX. Hanedan tapınağı olan, Büyük Ramses Anıt Tapınağı’nın (Ramesseum) arkasındaki mezardaki papiruslar gibi, basit, dikdörtgen, ahşap bir kutu içerisinde bulunuyorduChests are often represented standing on the ground in front of scribes. Five, almost complete papyrus rolls from a Dynasty V tomb at Gebelein, were found in a simple, rectangular, wooden box as were the papyri in a tomb behind the great Ramesseum, the Dynasty XIX temple of Ramesses III at Thebes. Although some boxes were labeled, they probably come from a kind of repository of royal personages. There is no evidence regarding the organization of a library in ancient Egypt before the great Museum-Library at Alexandra of the Ptolemaic Period, 332-30 B.C. There were royal administrative archives, where official daybooks, business letters and accounts were stored. Some were called “Place of Documents of Pharaoh” and there were also private repositories. Much information about the Greek civilization has come down to us through papyri. Egyptian papyrus became the basic writing material for the Greeks. In the Ptolemaic Period, when Greek pharaohs sat on the throne of Egypt, high quality papyrus production and trade was under royal ownership, a monopoly in the control of Pharaoh. It was also a material imported throughout the Near East. Papyrus was mainly used by the literati, for legal papers, and affairs of state. As C. H. Roberts noted:“Centuries before Alexander’s conquest had made the Greeks the masters of the country, Egypt had manufactured papyrus paper by a carefully guarded processes…. The Egyptians had made of it the finest writing material known…indeed, without such a relatively cheap and convenient material literature and the sciences could scarcely have developed as they did….” 7 Apparently Egypt was able to keep its process a deep secret and maintain its monopoly. Egypt went on to supply the whole Roman Empire. What a wonderful invention, so light, portable and easy to record information via a reed pen, compared to the “more cumbersome or more expensive writing material, such as stone and metal plates, wooden and clay tablets, or leather.” 8 But, alas, paper made of parchment arrived in the Second Century A.D. and later linen came along from China by way of Baghdad in the Eighth Century A.D. The fragile papyrus paper was no longer in demand. Luckily, though, many writings on papyrus by the ancient Egyptians did manage to survive, mainly in fragmented form. They are preserved in museums and institutions all over the world. The ancient Egyptians did not leave the method of making papyrus paper, but only wall paintings of its being collected. Although we have no record of how they produced the paper, modern scientists have experimented with the plant. The following steps are probably quite close to the method used: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Soak freshly cut stalks in water; Remove green rind; Split the soft pith in strips of finger width; Arrange strips side by side on a damp board; Arrange second layer of strips side by side atop the first strips in the opposite direction; Press the two layers together (pound with a mallet, or stone for several hours) and they become naturally stuck together by the sticky substance of the pith; 7. Leave the resultant sheet to dry; 8. Polish the paper with a piece of ivory, shell, or smooth stone to flatten and smooth roughness, 9. The ends can be overlapped and hammered together to make longer sheets. Fig. 9. Cast of the Narmer Palette. On loan to the McClung Museum from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Papyrus as a Symbol of Egypt The plant may have become the symbol of Lower Egypt as early as the fourth millennium BC. The plant is illustrated on one side of the famous Narmer palette of Dynasty I, circa 3100 B.C., a bronze replica of which is on exhibit in the McClung Museum’s Egyptian Gallery. Horus stands over his enemies, the marshland people of Lower Egypt symbolized by papyrus (Figure 9.). Another early example in relief are the papyrus stalks with round umbels on the well known fragment of an ivory club, now in the Cairo Museum. It depicts King Zer, or Scorpion King of Dynasty I, seated on his throne, with the plant in the background. Among the many fine examples is the relief at the Temple of Abu Simbel, built in Dynasty XIX by Rameses II, of a composite emblem of the twined plant symbolizing Lower Egypt in the “Union” of Upper and Lower Egypt. Papyrus Boats Uses for the plant were endless. They show the artistic, inventive and practical character of the ancient Egyptians in utilizing this most important natural resource that surrounded them. Even the Roman naturalist Pliny noted aspects of the plant’s diversity and wrote, “…indeed they plait papyrus to make boats, and they weave sails and matting from the bark and also cloth, blankets and ropes.” 9 For a culture that would not have existed were it not for the Nile River, boats were essential for survival. Egyptian men were the boat makers. They cut down and tied the papyrus stalks and carried them to a place where they could best construct them. There the mature papyrus stems were tightly bound together into an oblong slim shape. A light portable boat was the result. (Figure 10.). These boats were used to collect papyrus as it could navigate marshes. Also papyrus fibres were woven together and occasionally made into sails, or twisted into ropes for the small boats. Small skiffs were made by fishermen as they served well for fishing and laying of traps or drag-nets. The seams of the larger wooden boats were caulked with papyrus and the rigging was made of papyrus fibres. Papyrus was also used for light cabins on boats. Fig 10. A Boat Decorated with Papyrus. From G. Ebers, Egypt: Descriptive, Historical, and Picturesque. London 1879. James Bruce commented about additions made to a papyrus boat and its restriction to local use: “The Egyptian ships, at that time (Sesostris I, Middle Kingdom, 1971-1928 B.C.), were all made of reed papyrus, covered with skins or leather, a construction which no people could venture to present to the ocean.” 10 Ships of wood are known as early as the Old Kingdom. Some were as long as 100 feet, probably made of acacia, and some with papryus sails. Some had the stern and port carved in the shape of papyrus (Figure 11.). Fig. 11. Making a Papyrus Boat. From G. Wilkinson, The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians. London 1878. Papyrus in the Household Fig. 12. Woven Box on Stand. From G. Wilkinson, The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians. London 1878. Peasants as well as the wealthy had many useful items made of papyrus in their dwellings. According to Pliny the stalks were used as wood for fires but also to make utensils and containers. There were boxes, chests, crates and baskets to store goods such as wigs, toiletries, food, writing equipment (Figure 12.). There were bottle stoppers, balls and needle cases. Among other things papyrus rope was used in webbing for beds, woven floor mats and matting for walls. Papyrus curtains were made as doors that could be rolled up and down. Trays, stools with reed webbing, tables laden with food, and sandals are some of the household objects that were made of papyrus. Also, it was used for jar sealings. Amphora and other pottery vessels containing food and various liquids had the mouths sealed by papyrus. Some seals were woven and sometimes the papyrus was just stuffed in the jar mouth as a safeguard. Strands of papyrus pith were used as ties around documents and letters. Medical Papyrus Then there were numerous medical uses as is documented in the Ebers Papyrus and in the Edwin Smith Papyrus, a sample section of which is on exhibit in the McClung Museum’s Egyptian Gallery. Dried papyrus was used for expanding and drying fistulae and as an aid to open an abscess for the application of medicine. Burnt papyrus ash was a caustic remedy. Dioscorides (A.D.78 ) in the lst century A.D. wrote that the ash cures mouth ulcers from spreading. The ash was also used for diseases of the eye and if added to wine it induced sleep. The plant itself with water was known to cure skin calluses. Papyrus and Food Papyrus as food was mentioned by Herodotus, who said the annual plant was collected and the lower part eaten. The starch filled rhizomes were consumed raw or roasted and tasted even better after being baked in a red hot oven. The Greek botanist Theophrastus (ca. 370-288 B.C.) claimed it was of greatest use as food. Egyptians chewed the papyrus raw, swallowed the juice and spit out the remains. The Roman historian Diodorus of Sicily wrote, circa 60-30 B.C., that children were served stews along with raw, roasted, boiled, or baked, stalks of the plant. Pliny the Elder tells us that the root was a food for the peasant classes. He also noted that it was used as chewing gum both in the raw and boiled states. Fig. 13. Bastet Holding a Papyrus Scepter. From G. Wilkinson, The Manners and Customs of the ancient Egypians. London 1878. Papyrus as Amulets Amulets were worn suspended from a cord around the neck, as part of a broad collar, or sewn on mummy wrappings. One of the numerous faience amulets was the papyrus amulet, prized for its powers of regeneration, or rebirth as in renewed life. Another type of papyrus amulet was the hypocephalus, a circular piece of new papyrus inscribed with Chapter 162 from the “Book of the Dead.” Symbolic of the sun, the protective disk was placed beneath the head of the mummy to insure the deceased would have abundant warmth in the afterworld as on earth. Goddesses are depicted grasping a papyrus scepter, a long, thin shaft surmounted by a triangular umbel (Figure 13.). Papyrus for Floral Bouquets and Funeral Garlands Images painted on tomb walls frequently depict papyrus umbels used in feasts and funeral rites. Guests hold them in their hands at feasts, or praying persons in religious ceremonies. Servants carry papyrus stalks as common offerings to the gods. Papyrus was a precious gift on the altar and on the offering table in the temple. We also see the umbel as an ornament on walls, kisoks, tables, etc. In many tomb paintings there are depictions of “papyrus swathes” bundles of flowers and plant foliage tied around a central bunch of papyrus stalks. The feathery umbels on long stalks were ideal for these composite floral decorations in temples and tombs. It might be noted the stalks were used as a twine for attaching other flowers, the fibres used for stringing the flowers. The pith was shaped into artificial flowers. Fig. 14. Fowling Scene from the Tomb of Nakht. Copy by Richard Greene of Knoxville. Papyrus in Paintings and Reliefs Papyrus is represented in many paintings and temple reliefs as well as an important part of daily life. Among the numerous examples is the papyrus prominently featured in the wall painting of a marsh scene of fowling in the Dynasty XVIII Tomb of Nahkt at Thebes, which was recreated for the Egyptian Gallery of the McClung Museum. (Figure 14). Also is the fragment in the Metropolitan Museum of Art of a garden scene from from the tomb of Ipuy at Thebes, and in the Cairo Museum the painted papyrus clusters decorating the palace floor at Amarna. Sandstone reliefs at the mortuary temple of Rameses II at Abu Simbel depict prisoners strung together with papyrus and on painted friezes on the dais of the thrones of pharaohs. Papyrus and Architecture The papyrus symbol is often an essential feature in the small (Figure 15.) as well as the large.Towering papyrus form columns and pilasters in palaces and temples abound. Among many examples, the earliest is dated to the Dynasty III of the Old Kingdom, in the handsome papyrus-form pilasters on the building façade of the pyramid complex of King Djoser at Saqqara. The stalk on the pilaster is triangular in outline as is found on the plant. The style was replaced by the clustered type so common to later Egyptian temples. The Hypostyle Hall in the Temple of Amun at Karnak is an exceptional example (Figure 16.),the famous, scale model of which can be seen in the McClung Museum’s Egyptian Gallery. Fig. 15 Ointment box decorated wih papyrus. From Fig. 16. Model of the Hypostyle Hall. G. Wilkinson, On loan to the McClung Museum from the Metropolitan Museum of The Manners and Customs of the ancient Egyptians. Art. London 1878. Here the papyrus is full blown and in the round. The column tapers and is encircled by pointed leaves at its base and the capital in the form of an umbel. Also at Karnak is a towering pillar decorated in high relief with the symbolic papyrus stalks, erected by King Thutmosis III in Dynasty XVIII. Private dwellings were decorated with papyrus columns and pilasters as well. Papyrus Today Today, what might be the ancient species is now found growing naturally in the Wadi Natron, an oasis area just west of the Delta in Egypt as was mentioned earlier. This survivor may be the ancient species, but there are so many variants that problems have arisen in pinpointing the exact ancient plant species. Interestingly, a continuous growth of what some have judged to be the ancient plant is still profuse along the White Nile in the southern Sudan, some 1,500 miles south of the Egyptian border, alluded to by James Bruce. Various species of papyrus are found in other parts of the world, including the United States, and the continent of Africa such as in large areas of west, east and central Africa and on the island of Madegasca. The papyrus groves of Sicily are thought derived from papyrus introduced from Egypt by the Arabs in the 10th century A.D. * This paper was given Sunday, June 30, 2002, in the Frank H. McClung Museum at the Univeristy of Tennessee, Knoxville in conjunction with “Pharaoh’s Harvest,” a travelling exhibition about ancient and modern Egyptian plants, and also to provide a better understanding of the nature of the papyrus as exhibited in the McClung Museum's Egyptian Gallery. Notes 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Erman, Adolf, Life in Ancient Egypt. London: Macmillan and Co., 1894, p. 447. Herodotus, II, 92. Bruce, p. l. Tackholm and Drar, p. 134. Tackholm and Drar, p. 140. Cerny, p. 5. Roberts, p. 251. Cerny, p. 4. Pliny, XIII, 71. Bruce, vol. 1, p. 370. Selected Bibliography See Also: PDF version of the bibliography Basile, Corrado and Anna di Natale, Il museo del papiro di Siracusa , Quaderni dell’associazione istituto internazionale del papiro-Siracusa IV. Siracuse: Assessorrato dei Beni Culturali e Ambientali e della Pubblica Istruzione della Regione Siciliana, 1994. Bierbrier, M. L. (ed), Papyprus: Structure and Usage. British Museum Occasional Paper 60. London: British Museum, 1986. Breasted, James Henry, The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: published in facsimilie…. University of Chicago Oriental Institute Publications, v. 3-4. Chicago : University of Chicago Press , 1991 (from 1930 original). Cerny, Jaroslav, Paper & Books in Ancient Egypt . London : H.K. Lewis & Co, ca, 1947. -----------------, “The Contribution of the Study of Unofficial and Private Documents to the History of Pharaonic Egypt ” in Le Fonti indirette della storia egiziana. Studi Semitici 7. Rome : Univeristy of Rome , 1963, pp.31-57. Drenkhahn, Rosemarie, “Papyrus, -herstellung” in Lexikon der Ägyptologie. Wiesbaden : Otto Harrassowitz, 1982, 667 670. Lewis, Naphtali, Papyrus in Classical Antiquity. Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1974. Lucas, Alfred and J. R. Harris, Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries. London : Edward Arnold Ltd., 1962. Parkinson, Richard and Stephen Quirke, Papyrus. London : British Museum Press, 1995. Ragab, Hassan, Le Papyrus. Cairo : Dr. Ragab Papyrus Institute, 1980. Roberts, C. H., “The Greek Papyri” in S. R. K. Glanville (ed.), The Legacy of Egypt . Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1963, pp. 249-282. Tächholm, Vivi and Mohammed Drar, Flora of Egypt , Vol II. Bulletin of the Facultyof Science, No. 28. Cairo : Fouad I University Press, 1959, pp. 99-163. Kaynak: http://mcclungmuseum.utk.edu/research/reoccpap/reoccpr_pyrs.htm